“I hadn’t really noticed that I had a hearing problem. I just thought most people had given up on speaking clearly.”

Hal Linden

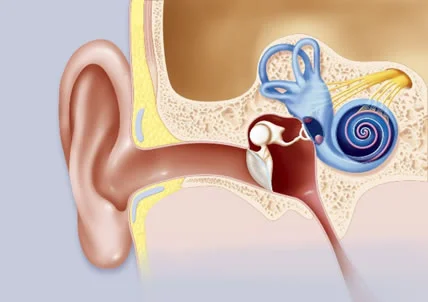

Scientists studying dementia (Griffiths, 2020) claim that midlife hearing loss is an independent risk factor for dementia, accounting for up to 9% of all cases. Acquired hearing loss is usually due to damage of the cochlea, the spiral-shaped bone in the inner ear which plays a vital role in hearing. It is known that cortical degeneration is seen in dementia. The researchers claim that there are many biological and psychological pathways that link auditory function to changes associated with dementia.

Griffiths explains that several auditory-cognitive links are plausible. Vascular changes often occur in Alzheimer’s disease and can also occur with cochlear damage. Hearing loss leads to decrease stimulation of cognitive processing. The brain needs stimulation for optimal function and lack of auditory unput creates an impoverished brain environment. People with hearing loss have less access to verbal and emotional communication and these are critical mediators for social interactions. Hearing is especially problematic for hearing impaired people in noisy environments, such as restaurants or parties and this difficulty can lead to social withdrawal. Lack of social stimulation is a well-known contributor to cognitive decline.

Hearing loss decreases active listening. Active listening is associated with positive effects on the hippocampus and on the structure of the auditory cortex. In a previous blog we discussed the low risk of cognitive decline in classical musicians who are highly skilled in the art of listening.

A third link is based on the theory that the hearing-impaired divert cognitive resources for listening, making these resources unavailable for other aspects of higher cognition such as thinking and memory because they are “occupied” during listening. Studies involving dual task paradigms provide a body of data to support this link.

A fourth link suggests that the cognitive auditory mechanisms located in the medial temporal lobe (which contains the hippocampus) may be linked to Alzheimer’s pathology in the same region. The specific pathology in link four is the neurofibrillary changes involving tau pathology. The temporal lobe is not traditionally thought of as part of the auditory system, but recent studies have shown that the hippocampus does respond to acoustic frequencies and is involved in memory processing for acoustic patterns.

An executive summary on dementia prevention published in The Lancet (Livingston, 2020) states that dementia is highly attributable to hearing loss. Furthermore, dementia risk is greater with increased severity of hearing loss. The authors reference a cross-sectional study of 6451 adults in the US which found a decrease in cognition with every 10 dB reduction in hearing. In another smaller study, they report that midlife hearing impairment, as measured by audiometry, is associated with steeper temporal volume loss, including the hippocampus. In a 25-year prospective study those using hearing aids did not experience dementia. Immediate and delayed recall deteriorated less with the initiation of hearing aids.

In an article published in JAMA Huang (2023) argues that hearing loss represents the largest modifiable risk factor for dementia prevention. Haung’s study analyzed results from the National Health and Aging Trend Study on 2431 Medicare recipients, half of whom were over the age of eighty. Results indicated a clear association between severe hearing loss and dementia with a 61% increase in dementia in people with moderate to severe hearing loss than in those with normal hearing. Use of hearing aids in this study was also associated with a 32% lower incidence of dementia.

Compliance with hearing aid use is notoriously low. In a sample of hearing aid users (Salonen, 2013), slightly more than half of the subjects said they used hearing aids every day. Twenty seven percent used hearing aids for more than six hours a day and 10% never used them. The most common reasons for minimal use were disturbing background noise, acoustic feedback problems, battery cost, and a lack of motivation to use the hearing aid.

Hearing loss is a highly modifiable risk factor for dementia. Oder adults should be screened for hearing loss and hearing aid users should be counseled to use hearing aids consistently. The quality of hearing aids has improved and for some, refitting with newer models may increase compliance.

References

Griffiths, T. D., Lad, M., Kumar, S., et al. (2020). How Can Hearing Loss Cause Dementia? Neuron, 108(3), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.003

Huang AR, Jiang K, Lin FR, et al. (2023). Hearing Loss and Dementia Prevalence in Older Adults in the US. JAMA. 329(2):171–173. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.20954

Livingston, G, Huntley, J, Sommerlad, A, et al. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care:2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet Commission, 396(10248): 413- 446.

Salonen, J., Johansson, R., Karjalainen, S., et al. (2013). Hearing aid compliance in the elderly. B-ENT, 9(1), 23–28.